About

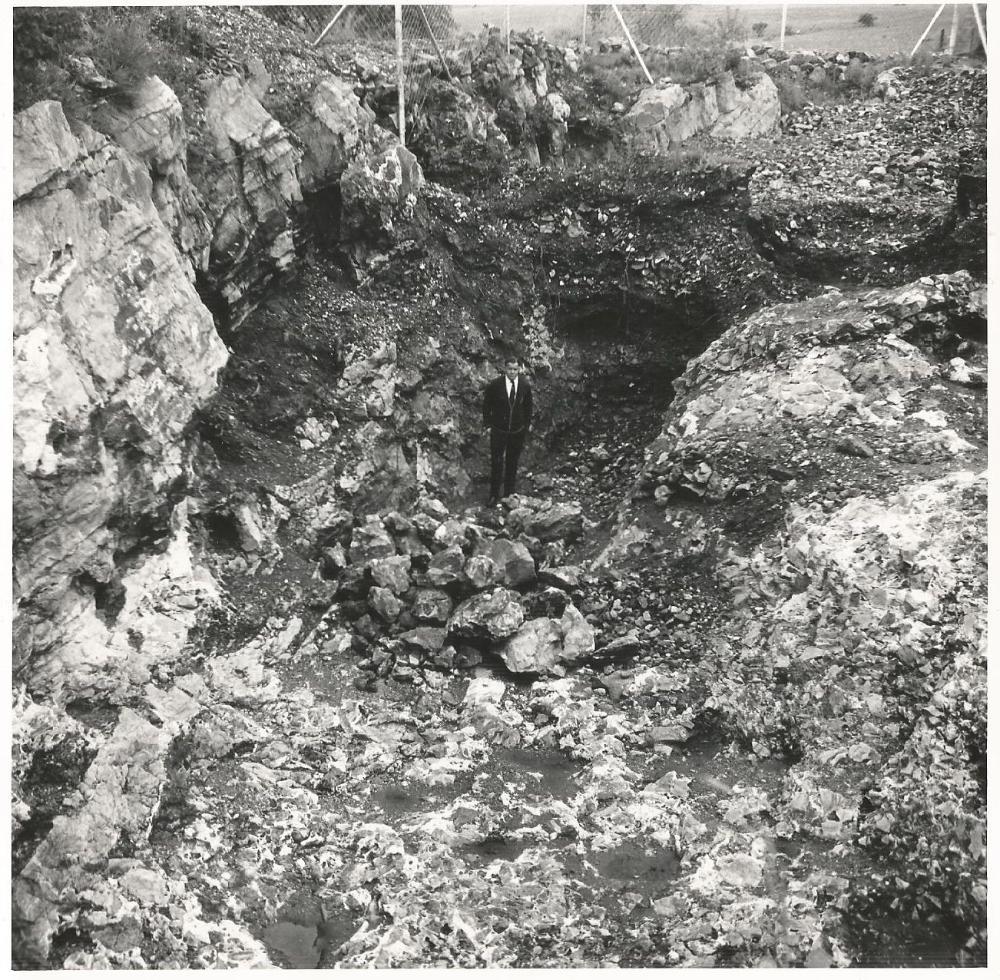

The Sterkfontein and Swartkrans Caves are globally significant heritage sites, known internationally for their fundamental contributions to the field of palaeoanthropology. An active research program continues at both sites while exciting historical collections yielded from previous excavations represent some of the most widely studied and published hominin materials

In addition, Sterkfontein has been the only publicly accessible large cave in the Cradle of Humankind for many years and attracts between 80,000 and 100,000 visitors a year for the cave tour and small museum. It is a major tourist destination in Gauteng and hosts tens of thousands

of school learners a year for tours of the caves.

Since 2001, the tourist operations at the Sterkfontein Caves were operated by Maropeng as part of the Cradle of Humankind UNESCO World Heritage Site interpretation centre. As of April 1, 2024, following the optimal reconfiguration of the partnership, Wits, through its Faculty of Science, is now responsible for all research and visitor operations at the Sterkfontein and Swartkrans Caves.

The research led, public facing entity will serve as a heritage, research and science communication hub for Wits in the Cradle of Humankind, hosting research field trips, field schools, workshops and researchers from Wits and international institutions studying the diverse and ancient Cradle landscape, science communications, museumology, and forensic anthropology in a dynamic public-facing environment. No similar facility exists in the Cradle of Humankind.

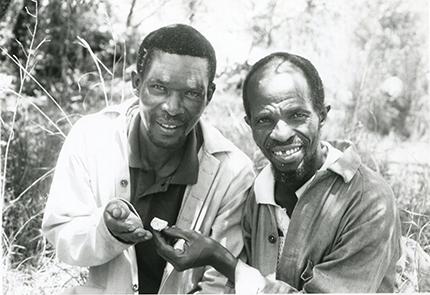

Meet the Team

MANAGEMENT |

|---|

Job Kibii - Head: Sterkfontein Caves |

Ntobeko Mbuyisa - Operations Manager |

Dominic Stratford - Associate Professor (Archaeology) |

GUIDES |

TECHNICAL TEAMS |

RESEARCH PERMIT HOLDERS |

|---|---|---|

Kenneth Mawete |

Lucas Sekowe |

Dominic Stratford |

Martina Van Adrichem |

Andrew Phaswana |

Matt Caruana |

Mpho Malogadihlare |

Abel Molepolle |

Recognise Sambo |

Trevor Buthelezi |

Sipho Makhele |

Maryke Horn |

Itumeleng Molefe |